The baby and the bath water: adult cardiac stem cells revisited

Apr 30, 2025

Originally published here

Heart failure (HF), the progressive disorder with >50% mortality 5 years after onset, is due to a deficit in cardiomyocyte number and/or function. Despite remarkable treatment advances, HF remains a major challenge in cardiovascular medicine because, except for heart transplant, none of the available therapy stably restores the deficit in functional cardiomyocytes.

Evidence that soon after birth cardiomyocytes become terminally differentiated and unable to re-enter the cell cycle led to the conclusion that the adult heart was a terminally differentiated organ unable to generate new myocytes, a conclusion reinforced by the rare existence of cardiac neoplasias.1 This implied that, from cradle to grave, life depended on the cohort of cardiomyocytes present shortly after birth but inexorably decreasing in number by the wear and tear of the uninterrupted heartbeat.

The discovery that tissue-specific adult stem cells are responsible for the cellular homeostasis and regeneration of most adult organs, including the brain, left the heart, despite its indispensability for organism survival, as the only major organ unable to generate new parenchymal cells throughout life. This biological exceptionalism of the heart was finally challenged by demonstration of the slow but continuous appearance of new cardiomyocytes throughout life, followed by the identification, isolation, and characterization of a rare population of myocardial cells with all the expected characteristics of an adult cardiac stem cell.2 Yet, the exceptionalism of the heart as a non-regenerative organ mostly remains ingrained in the cardiovascular community.

The cardiac stem cells

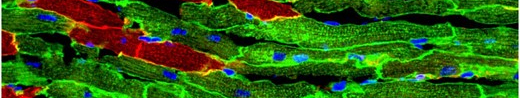

A small sub-population of c-kit+ adult myocardial cells was shown to be self-renewing, clonogenic and multipotent in vivo and in vitro.2,3 When properly stimulated these cells give origin to the four main myocardial cell types: spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes, smooth and endothelial vascular cells, and fibroblasts.2,3 Demonstration that the progeny of one of these cells expanded in vitro (a clone) transplanted, either intramyocardically or through the systemic circulation, homes and nests into damaged myocardium where it generates new myocytes and micro vessels, justified calling them cardiac stem cells (CSCs).3–5 Their presence has been identified in all mammalian species studied, from mice to human, by a plethora of independent investigators. Nonetheless, only ∼1% of the myocardial c-kit+ cells are CSCs; the rest are blood-borne cells and endothelial cells and precursors.5,6 Until now, not a single CSC-specific membrane marker has been found to allow for clear identification and direct isolation. Therefore, their isolation depends on cumbersome exclusion of endothelial and blood lineage cells from the c-kit+ cell population.6

Identification of the CSCs not only challenged the cellular exceptionalism of the heart as a terminally differentiated and non-self-renewing organ but also, concurrently, opened the tantalizing prospect of cellular cardiac regeneration as a potential therapeutic avenue to prevent or treat HF. That heterologous CSCs transplanted into an acutely infarcted heart, through their paracrine effect, stimulated autologous regeneration raised the prospect of a widely available and affordable therapy to prevent or ameliorate HF, a frequent delayed consequence of large MIs.

The controversies

As often happens in response to paradigmatic shifts, the initial broad interest elicited in potential myocardial regeneration was rapidly followed by questions and scepticism about its nature and physiological significance. First, doubts about the physiological import of the CSCs were raised because, clearly, they cannot regenerate the myocyte losses caused by an MI. These questions ignored the fact that endogenous tissue regeneration, even in the most regenerative tissues, repairs wear and tear damage but not the tissue losses produced by occlusion of segmental arteries. Second, because no CSC membrane marker is specific to and exclusive of these cells, different groups described cardiomyocyte precursor cells using their preferred marker (c-kit, Sca-1, MDR-1, Abcg2, Isl1, and so forth), with the puzzling consequence that the adult heart, for decades considered a post-mitotic organ, ended up with an astonishing number of apparently different CSCs.6 Subsequent work showed that the different markers were either co-expressed by the same cell or at different physiological, differentiation or activation stages of the same cell lineage. Yet, the lack of a CSC-specific identifying membrane marker remains a source of confusion. Third, recent attempts to genetically determine the fate of the CSCs and identify their progeny7 have almost destroyed this nascent field. Not surprisingly, using c-kit and other non-specific genes expressed in the CSCs, Cre-lox (and other similar site-specific recombinase systems) cell-fate mapping studies failed to show a significant contribution of the CSCs to new cardiomyocyte formation during development, in adulthood or after injury, with concomitant denial of the existence of any resident adult cardiomyocyte progenitor cells.7 However, because the generation of new cardiomyocytes in adulthood could no longer be denied, the failed cell-fate mapping studies were swiftly followed by reports claiming that the main/sole source of adult neo-cardiomyogenesis was the replication of adult and terminally differentiated myocytes!.7